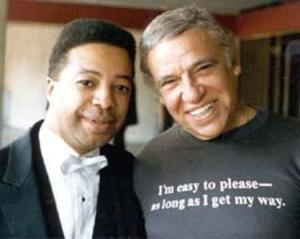

(Tony Williams and Buddy Rich. Image lifted from Vince Wilburn, Jr.’s Twitter feed)

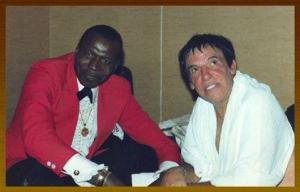

(Elvin Jones and Buddy Rich. Image lifted from Dave Liebman’s Facebook. Both these photos showed up on Mark Stryker’s Twitter, that’s how I found them. See also Mark’s guest post “Traps, the Drum Wonder.”)

—

There have been many think pieces about Whiplash, a movie that most general filmgoers have celebrated and a few jazz musicians have hated.

While the movie is still hot, I’m going to make a few points that seem really obvious to me but that I haven’t yet read elsewhere. My commentary here comes paired with Mark Stryker’s guest post “Traps, the Drum Wonder.”

—

This post is about 6000 words but it still isn’t long enough. Hoping to move reasonably freely, I’ve made this special button. If possible, please keep this button in mind when reading.

—

Tootie Heath says that in the really old tradition, when a musician sits down to play a concert, it is very important for the musician not to have worked on music yet that day. The player’s mind should be fresh, and they should ask the ancestors for permission to create. Everyone in the circle should be on the same fresh page, ready to respond not just to all the other musicians in the circle but also to the primordial reason to play music.

This is a devotional attitude, an African attitude.

—

Most of the rhythms that power American music come from Africa. They were brought here on the slave ships. In shorthand form, all our beloved New World music mixes European harmony and African rhythm. (There are melodic contours that are African, and rhythm technology that is European, but that’s the basic mix. Cuba, the rest of Latin America, and everything else that Jelly Roll Morton called “the Spanish tinge” is crucial—although some argue that Africa was the source of all those different rhythms, too.)

—

The devotional attitude of African rhythm is one reason it’s so compelling. African rhythm seeks ecstasy through communion, not just with God but with everyone in the immediate vicinity. You don’t practice it. You plug into the ancestors and your reason for living and it’s there.

There’s intimacy and devotion in European music as well—J.S. Bach inscribed even small exercises “to the glory of God”—but society usually views the symphonic concert or grand opera as the highest aspirations of the form. Many of my own favorite pieces are piano concertos, which celebrate the virtuoso soloist almost as much as the composer. Both composer and soloist are placed on a high platform.

No such high platform exists in classical African music. There are still drum or vocal virtuosos, of course, but devotion and interconnectedness come first.

—

You don’t need to be in Africa to get that interconnected feeling. Any time everybody in the room is on the same page you can get it. Surely that feeling must exist in all cultures in different ways at different times. However, the African version was especially crucial for American music.

—

Early jazz had the impact it had because of the feeling. Duke Ellington explained it best in his autobiography, talking about a club in 1920’s Harlem:

Sonny Greer and I were real tight buddies and, naturally, night creatures. Our first night out in New York we got all dressed up and went down to the Capitol Palace…

My first impression of The Lion – even before I saw him – was the thing I felt as I walked down those steps. A strange thing. A square-type fellow might say, “This joint is jumping,” but to those who become acclimatized – the tempo was the lope – actually everything and everybody seemed to be doing whatever they were doing in the tempo The Lion’s group was laying down. The walls and furniture seemed to lean understandingly – one of the strangest and greatest sensations I ever had. The waiters served in that tempo; everybody who had to walk in, out, or around the place walked with a beat.

Sonny Greer is Duke’s drummer here. He played the drum set on all of Duke’s most famous early records.

—

A drum set. What is a drum set?

A drum set is a version of an African drum choir reduced and streamlined so that a single musician can provide that devotional feel for a larger ensemble.

All the greatest American drummers specialize in “feel.” I am not an expert in this topic, but as a big jazz fan, I know that “feel” is what makes the music go.

Most great jazz needs a great drummer.

—

Not all grooving music needs a drummer for “feel.” The classic instrumental quintets of American Bluegrass and Argentinian Tango seem to do better if a drummer stays well away.

But for most jazz, there’s a drummer present.

—

Good drummer in the band: good jazz.

Bad drummer in the band: bad jazz.

—

A lot rides on the drummer because they are often the only one connecting all the rhythmic dots. That can be a lonely position. While fiction, a bit from a disgruntled teenager in Up for It: A Tale of the Underground by L. F. Haines (collected in Best African American Fiction 2010) will certainly get a nod of rueful recognition from any professional drummer:

It was something to drive a band, more than a notion, let me tell you. And understand this, pilgrims: Drummers are damn important to a band. I don’t care what you’ve heard otherwise. If they don’t get the rhythm right, they throw the whole band off and nobody can play right. Being a little bit slow on the beat or rushing the tempo can mess up things real bad because a band is a delicate thing, like a clock or a race car or something, and you’ve got to have good coordination. We drummers do more than keep time but keeping time well is very important. And we get tired of hearing people say we play too loud. If the other retards in any given band would learn something about harmony and dynamics, then we wouldn’t need to play so damn loud. We’re not trying to overshadow the band; we’re trying to make sure the damn band can hear us and know where the damn beat is. But don’t get me started. Drummers get no respect!

Of course, Haines is not talking about immortal jazz groups led by, say, Miles Davis or John Coltrane: In those bands, everyone is connecting the rhythmic dots, that’s part of what makes that music so great.

—

At the top of the page there are pictures of Tony Williams and Elvin Jones. They are two of the drummers associated with Miles Davis and John Coltrane. They are total devotional players. With Tony and Elvin, feel is the most important thing. It is impossible for me to imagine them picking up a stick without swinging.

Tony and Elvin are famous for playing a lot of virtuosic and innovative drums as well. Part of this was their natural inclination, but part of it was coming to prominence with Miles or Trane in groups of overall rhythmic excellence. Their aggressive and unusual permutations were part of a bigger circle of devotional music, where all members in the circle were innovative.

Tony and Elvin were great drum soloists, but I don’t think any of their fans would play a drum solo of either to prove they were great. A fan would play Tony or Elvin while the whole band was improvising together.

Drum solos are like a piano concerto: a platform for the celebration of one. With all their chops and innovative ideas, Tony and Elvin seldom stopped and got on that platform for too long. They take unaccompanied star turns, sure, but soon enough the band will come back in and the devotional circle will recommence.

—

The other drummer in the photos above is Buddy Rich.

Buddy Rich is the biggest inspiration for the young drummer portrayed in Whiplash, and score composer Justin Hurwitz explicitly cites Rich in an interview in The Credits:

Hurwitz said one of the things he’s most proud of is an overture which plays twice in the film, tentatively at first, much like Andrew is at the time, then boisterously and bombastically at the end. “Andrew is walking through New York in the second scene, and there’s an abridged movement that plays. Then at the end credits, the full four minute version of that song plays. I modeled it after the Buddy Rich big band style, it’s very, very fast, complicated and dense big band music, the band is just flying around playing, interweaving lines.”

—

Buddy Rich had a long career. A total natural, Rich was a monstrously talented drummer from an extremely young age.

His specialty was chops. His hands. Rudiments, rolls, cadences: the stock-in-trade of military snare drums, going back hundreds of years to Europe and other places.

How fast and flashy were Buddy Rich’s hands? For many, they were the fastest and flashiest ever.

—

Why are fast and flashy hands important in a jazz drummer? The short answer: they aren’t.

The equation

Good drummer in the band: good jazz.

Bad drummer in the band: bad jazz.

has very little to do with the drummer’s fast and flashy hands. It has much more to do with the drummer’s devotion and feel.

Some of the cognoscenti’s best-loved jazz drummers had hands only fast enough to go to church every time they sat behind the kit.

Some of those giants would barely even take a solo.

—

A story about Mel Lewis: Mel hated giving lessons, but finally a kid talked him into letting him come by a record session so that he could watch Mel at work. During a break, Mel gestured for the kid to sit behind the kit and said, “Play me a snare roll.”

The kid played a good, professional roll. Maybe not as good as the one that starts the movie Whiplash, but still, a good roll. Not easy to do.

Mel took his sticks back and said, “See, right there is your problem. You shouldn’t be able to do that. I can’t do that. You gotta quit that shit and start becoming a drummer.”

—

That’s a fun story, but truthfully drummers do need to learn how to roll. Mel himself surely learned to roll at some early point.

However the point is clear. At least for Mel Lewis, devotion takes precedence over chops.

Another way to say it is: After you are good enough to learn your military rudiments, are you good enough to let them take a back seat to feel?

—

—

Mel Lewis was a white big-band drummer. He made a point to play in a style that de-emphasized chops. This is not the way most historically important white big-band drummers play.

—

Gene Krupa was the first star big-band drummer. He would stop Benny Goodman’s band and take fancy solos. At those points it was really like a European piano concerto, with a full assortment of back-up band waiting around as the featured soloist worked up to a frenzy.

Krupa’s most famous performance is “Sing, Sing, Sing” with Goodman at Carnegie Hall. It’s great, and I particularly admire Jess Stacy’s surreal and romantic piano solo. Talk about Europe meets drums!

—

Buddy Rich was Krupa’s disciple, and soon surpassed Krupa in drum antics and theatrics.

Later in life, Rich would cram everything he could into every corner while his big band was roaring along. The classic Rich “concerto” was a medley of West Side Story themes where Rich would play almost as much during the band parts as during the solos.

This hyperactivity is why some consider him the greatest drummer. In countless polls, over decades, Rich has been at the top. Not in the jazz polls at this point. But in the rock or general interest polls, Buddy is still top dog.

A recent Consequence of Sound poll of (supposedly) “thousands of thousands” weighing in on “The Greatest Drummer in History” has Buddy Rich in the final tabulation alongside various rock greats. Rich is the only jazz drummer these people know, apparently.

Almost certainly, all those people who would claim that Rich is the greatest ever would offer up one of his solos, not his devotional position within a group.

—

Whiplash is rather retrograde in suggesting that the fancy drum solo is a centerpiece of American entertainment connected to jazz. That era was the Forties and Fifties.

The term “stage band drumming” is relevant. “Stage band” suggests a big band in a floor show Las Vegas, playing for burlesque, crooners, dinner, dancing, and the occasional hot instrumental capped by drum fireworks and a final blaring “Ta-dah!”

Johnny Carson had a stage band: the Doc Severinsen organization with Ed Shaughnessy on drums. Carson loved drums and Shaughnessy had quite a few solo features over the years.

Interestingly, Dave Letterman also loves drums and fairly recently had “drum solo week” on his show. Neil Peart took a solo that included pre-programmed “swing” big-band hits from his massive rig of pads, computers, and a few hundred drums. Clearly Peart knows his stage band history.

—

Right, rock drums. Rock drum solos! Everyone leaves the stage while the drummer goes animal for 15 minutes!

Yep, straight out of stage band. And straight out of Buddy Rich, whose solos are usually namechecked by all the rock drummers when discussing their own epic solo moments.

It seems to help to have a lot of drums, cymbals, and other ways to make cascades of sound when crafting a major rock drum solo. Jazz drummers prioritizing devotion and interconnectedness usually use a minimal amount of gear.

—

Generally, the great black jazz drummers are not in the stage band tradition. Not to say there weren’t any good ones! But great black jazz has always been more about getting the feel right then fast and fancy hands.

Still, respect must be given: Chick Webb was an important innovator of flashy big-band drumming and apparently an influence on Krupa, but he also died very young. Sid Catlett also died too young, but not before taking one of the first recorded long drum solos on “Mop Mop” with Louis Armstrong at Symphony Hall in 1947. (I have heard that Jack DeJohnette can play this iconic solo complete.)

—

Max Roach is usually considered the premier modern jazz drum soloist. On “Ko-Ko” with Charlie Parker, Roach’s solo statement answers Bird in a way essential for the projection of bebop’s uptempo emotional message.

Roach would also record what were among the very first drum solo compositions on Drums Unlimited. However, the title track “The Drum Also Waltzes” and “Big Sid” are more showcases for feel, composition, and bebop language than for fancy theatrics (not that Roach doesn’t have amazing chops).

On Rich vs. Roach, the track “Figure Eights” offers uptempo trades. Buddy certainly seems louder and more precise, although the drum tuning and recording levels may have something to do with it as well. No one’s snare drum sounds more like a machine gun than Buddy Rich’s snare drum.

For me, Rich vs. Roach is just a curio.

—

The most popular black bandleaders Duke Ellington and Count Basie had some of the great black big band drummers. Basie’s first, Jo Jones, helped define what swing was for all jazz for all time.

Tootie has an amusing story about Jones’s relationship to Rich (who adored Jones): “I saw Jo Jones sub for Buddy Rich once in Buddy’s big band. When Jo came in, the first thing he did was ask the whole trumpet section to put mutes in. Then he played the whole gig on brushes!”

That’s one way to get the band to listen up to the drummer’s beat: have the band play softer.

I’ve written about Sonny Greer extensively already in my post on Ellington, “Reverential Gesture.” He was great but not well-loved by those whose ideal was Buddy Rich.

Interestingly, while Basie’s postwar band book became more flashy, with the drummer required to set up hits all the time, Ellington almost always had someone like Sam Woodyard, someone who functioned more independently from the orchestra.

—

When the crowd-pleasing drum solo became popular, both Ellington and Basie offered interesting solutions. Ellington got a white cat, Louis Bellson, and in 1952 tracked a piece of immortal fancy drums in one of the best acoustics ever gotten for drums on tape. Duke gave Bellson full compositional credit but I wonder who came up with the name: “Skin Deep.”

In the later Fifties, Basie gave his black drummer Sonny Payne a solo feature. Payne’s choice of repertoire also has an interesting title: “Ol’ Man River.” Payne would actually play the Kern tune (a protest against slavery written for Paul Robeson) on his toms.

—

Krupa, Rich, Bellson, Shaughnessy: those are probably the most famous stage band drummers.

Bellson fared best with the cognoscenti, partly because he always said publicly that Duke Ellington was his career highlight and married a black woman, the major talent Pearl Bailey. The first time I saw Bellson play he was late in life yet onstage at Newport with Dizzy Gillespie, Ron Carter, and other major black figures.

Krupa, Rich, and Shaughnessy, all great drummers, all followed similar career tracks. In the beginning they were in with the cognoscenti and made records with significant black jazz musicians. Devotion was unquestionably present. But, as they become general-interest stars, they seemed to be mostly connected to the white world of money and power.

I’m sure they could all still swing, but it was really the flashy hands, not the devotion, that got them that career track.

Bellson has more credibility. Mel Lewis has much credibility. And going further back, the white cat who was the delightful alternative to Krupa was Dave Tough, the quiet and devotional drummer for Woody Herman, the Forties white band that proudly proclaimed it could play the blues.

—

“Playing the blues” began as a black thing, but soon enough it pervaded all of American music.

The great musical big-band love of white America during World War II was Glenn Miller, whose group played the most sanitized swing and blues imaginable. I nominate Moe Purtill’s fills in “Tuxedo Junction” (1940) as the least swinging drum fills ever heard on a popular jazz record.

Miller’s performance style wasn’t that hip, but it’s still good enough to dance to. I’m sure plenty of black couples have cut a rug to Glenn Miller over the years.

—

—

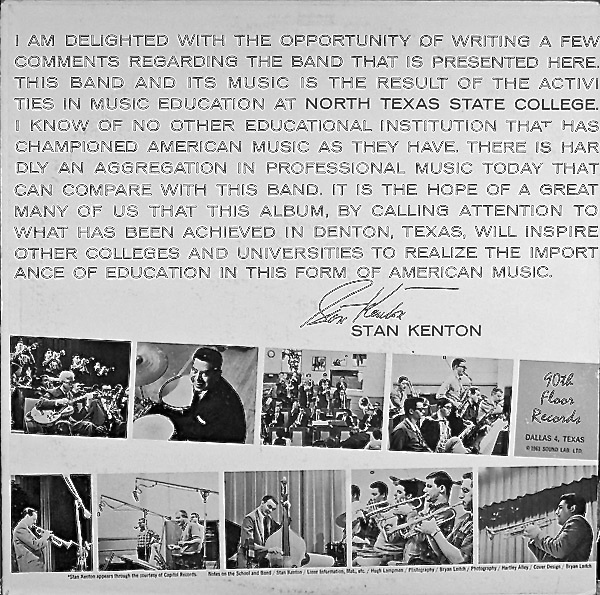

In the next decade, some white big-band music took a sharp turn into the undanceable with Stan Kenton, whose noisy “music of the future” repertoire gets a fairly bad rap among the cognoscenti today. Truthfully there are Kenton performances that are important works of jazz.

Kenton’s band was also deeply connected to the birth of jazz education. North Texas State University was key, where there was some kind of military attention to ranking and lock-step detail that is the true father of the school system depicted in Whiplash.

From the Wikipedia entry on the One O’Clock Lab Band:

The One O’Clock evolved from an extracurricular stage band founded in 1927 into a curricular laboratory dance band in 1947 when North Texas launched the first jazz degree program in the world. For the next 20 years — until 1967 — North Texas was the only US university that offered a degree in jazz studies.

And from the Wikipedia entry on Stan Kenton Band Clinics:

Dr. Gene Hall and Leon Breeden, both of North Texas State University, played a major role in helping Kenton develop the clinics.

The first clinic was in 1959, held at Indiana University under the auspices of the National Stage Band Camp. Struck by the serious responsibility and encouraged by his first camp, Kenton, in 1960, sent a trunk load of original big band scores culled from his library to North Texas for use as teaching aids.

(Cover of first North Texas State jazz LP, 1961)

For years, at least since Kenton and Leon Breeden began to be reputed for “Lab” music from Denton, Texas, there has been a symbiosis between bands, schools, gear, and jazz magazines. The latest brilliantly marketable vehicle is the Gordon Goodwin Big Phat Band. Phat drummer Bernie Dresels’s video on YouTube “Flashy Snare Drum Licks” has been viewed over 200,000 times and boasts a truly astonishing collection of over 200 inane (high school age?) comments. Dresel name-checks Buddy Rich in the first 30 seconds.

I don’t mean to hate on North Texas State, Breeden, Goodwin, Dresel, or anything else, but none of them are part of a serious discussion of modern jazz, at least as far as I know…

… On the other hand, Goodwin just won a Phat Grammy and Whiplash is a hit movie, so maybe I really need to wise up.

—

Kenton’s best music leads straight into futuristic late-Sixties and Seventies white big-band leader Don Ellis, famous for odd-meters.

Ellis was hipper than Kenton, probably, and I don’t ever mind hearing his music, especially that early small group stuff with Jaki Byard or Paul Bley. The odd-meter big-band material certainly has its place as well.

—

—

The black alternative to modernist jazz big band Kenton, North Texas State “Lab,” and Ellis was the Sun Ra Arkestra, who combined the old-time swing religion of Fletcher Henderson with the weirdest shit imaginable. They were a group so devotional that they essentially lived their whole lives together.

As Kenton, “Lab,” and Ellis recede from historical view, Sun Ra just keeps seeming more important. This is only correct.

—

The 1973 chart “Whiplash” in 7/4 meter was written for Ellis by Hank Levy. It’s a flowing and cinematic piece, and while no modern jazz professional would think it is a particularly advanced treatment of odd-meter in 2015, back then it was still innovative to sound this relaxed in seven. Kudos to the drummer on “Whiplash,” Ralph Humphrey, who also played with the other leader of that era’s odd meters, Frank Zappa.

In general Ellis’s version is better than the movie cover, although, to be fair, the uptight soundtrack version does sound like student band. (So, better for the movie, maybe?)

Also featured on the soundtrack is “Upswingin,” by Tim Simonec (secondary composer of Whiplash score), which places the Krupa “Sing, Sing, Sing” beat in seven.

Seven is odd, but not as odd as it could be: When I was a (terrible) drummer in my own high school jazz band, the ultimate challenge was Ellis’s “The Last Tangle of Lord Boogie” in 13/8.

Nobody could play it. Horace Silver’s “Filthy McNasty” was much easier.

Except, of course, now I know the devotional shuffle of “Filthy McNasty” is much harder than farting around in 13/8 for “The Last Tangle of Lord Boogie.” Too bad I didn’t have a mentor to explain that to me.

—-

—

Odd-meters are easy to teach and a good way to improve reading and rhythmic awareness. That’s one reason odd-meters are favorites of school bands.

Of course, there’s also plenty of wonderful and essential music that requires odd-meter.

The relationship of devotional groove and odd-meter is hard to parse. Most jazz drummers appropriate some Afro-Cuban, and the music of virtuosos like Los Muñequitos de Matanzas has some of the oddest phrases I’ve ever heard. However, those odd groupings happen within an even folkloric framework. In jazz, part of what creates swing is a hint of those kinds of odd groupings. See especially Elvin Jones and Art Blakey.

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is sometimes cited as the first work proposing odd-meter vamps. This is exciting rhythm, but it’s not folkloric. It’s a composer seeking something new.

Devotional odd-meter certainly exists, though, especially when you add in the classical drum music of other cultures, perhaps especially the rich traditions of India. In Africa, certain Pygmy music is in odd-meter.

—

Max Roach was reputedly furious that Joe Morello got the first 5/4 drum solo on record with the Paul Desmond/Dave Brubeck “Take Five” (1959). He claimed that he’d done it first, but that the studio wouldn’t put it out. (In 1956, Max did record a wild arrangement of “Love is a Many-Splendored Thing” with a few bars of five, before Morello.)

Again on Roach’s Drums Unlimited (1966), “Nommo” was in 7/4. Unlike the cheerful “Take Five” and “Unsquare Dance” titles of the Brubeck/Morello crew, Jymie Merritt’s title refers the mythological ancestral spirits of Mali. They wanted the cognoscenti to know right away that this band was still devotional while taking it odd!

—

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s article on reparations for African-Americans has been one of the key political ideas in recent memory.

At first glance it was hard to for me to see how to apply the “reparations” concept to jazz. History is the ultimate judge of artistic merit, and history has generally taken care of imbalances in the long view of jazz reception.

Usually, from where I sit at this moment, among the people I know and trust, things are in their proper place. Benny Goodman isn’t considered greater than Duke Ellington; Dave Brubeck isn’t considered greater than Thelonious Monk. Not that Goodman or Brubeck weren’t valuable musicians, but, c’mon.

However, this Whiplash scandal offers a plausible starting point for jazz reparations. From the same interview with the film’s composer Justin Hurwitz:

Hurwitz plays the piano, yet his education was mostly classical without much of a jazz background. “It’s a huge regret looking back because it’s just such a different language, and it’s a little like spoken languages where the younger you are the easier and better you soak up the rules and syntax of all of it.” Yet Hurwitz has gotten an intensive jazz program working on Chazelle’s last two films. “Damien put me on a steady diet of jazz, both American and French music scores,” he says. “Basically I had an independent study with Damien the last couple of years of college. Now I use more jazz idioms today than I learned in musical theory class.”

This movie not only celebrates a Buddy Rich-style ideal but the person in charge of the music learned about jazz after becoming a professional film score composer. Hurwitz even admits to studying jazz “French scores.”

—-

This is where I get jealous of hip-hop. Hip-hop has guarded its black sovereignty so well. Forty years after the genre was born the question of who gets to be a hip-hop star remains a racial flashpoint.

Imagine if for a movie about hip-hop, the composer said he was new to the style, so he studied Eminem and Iggy Azalea, not to mention the founding father of French spoken word and sexy style, Serge Gainsbourg.

—-

Nobody in jazz these days plays to predominantly black gatekeepers or audiences, whether in the clubs or in the schools. It’s essentially an esoteric art music for those who love it, everybody welcome—because we truly do need every goddamn fan we can get!

Naturally, the more black people involved the better. Unfortunately, when the topic of contemporary jazz comes up, it feels as if—although I don’t know for sure!—much of the black intelligentsia isn’t that interested.

I admire Jamelle Bouie, not just for his acute political writings but his sincere engagement with a larger spectrum of culture, from comic books to movies to heirloom beans.

So when Bouie recently let loose with multiple tweets endorsing Whiplash, he broke my heart a little bit.

On the other hand, why would Bouie know that there was anything wrong with Whiplash? That was just some jazz stuff, right? Got nothing to do with real black music like hip-hop.

(Cue a scribe from Nicholas Payton; perhaps start with this one, “Black American Music and the Jazz Tradition.”)

—

Coates said to Stephen Colbert when explaining reparations, “… The damage is such that it doesn’t go away when we don’t talk about it. New things happen that are compiled on top of that damage.”

—

My wife says that if you think Rocky Marciano is the greatest boxer, you are racist.

In light of the Whiplash phenomenon, I have no problem saying that if you think Buddy Rich is the greatest jazz drummer, you are racist.

It’s a perception that just has to change. When it does change—for example, when we collectively understand the annihilation of the devotional African aesthetic from Whiplash—we can go back to admiring Mr. Buddy Rich for his undoubted excellence.

Until that change, dues need to be paid.

[End.]

[Update, 2016: Recently Rolling Stone offered a ranked list of the 100 greatest drummers. They claim to deal with rock, not jazz, yet somehow Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa place ahead of Elvin Jones and Tony Williams. This essay had far reach when published in 2015, including praise from Donald Fagen when writing a diary for Rolling Stone. Not that I expected to single-handedly change embedded institutional racism with this think piece, but still, I was shocked at the unspeakable glibness of Rolling Stone’s recent list.]

—-

Can’t get enough? A dozen more drum fills that didn’t quite fit in the essay:

Ba Da Boom 1: Miles Teller may play a bit of drums, and just maybe Teller makes some of the sounds heard in the movie, but in general Teller is not the drummer on the soundtrack. I’ve listened to the soundtrack carefully and have concluded that the unknown drummer or drummers are actually the most experienced musicians in the band.

Presumably the soundtrack drummer was placed under a gag order in order to help give the impression that Teller is actually drumming. It’s too bad, because this is a real opportunity to get some gigs!

The booklet for the soundtrack lists no personnel. This isn’t the first soundtrack I’ve seen with this arrogant stance, but for a “jazz” group with solos, etc., denying attribution is particularly reprehensible.

The credits in the movie do not list personnel, either.

To be fair, I don’t understand film scoring or the relationship of director to composer. This dual interview of Justin Hurwitz and Tim Simonec is like reading a foreign language.

Simonec: Working with Damien Chazelle, who is a drummer and has a great love of big band music, made the composition process extremely smooth and efficient. He was able to perfectly articulate the kind of compositions he wanted for each scene.

If I had gotten the gig, I wouldn’t have lasted a day.

Ba Da Boom 2: Why a Don Ellis tune? That seems like a reach, a strange choice.

Now in the realm of total speculation: in an interview, editor Tom Cross (who won an Oscar for his editing of Whiplash) mentions an inspiration for the director and himself:

In approaching that scene, they also referenced the car chase from The French Connection and the way that scene incorporated Gene Hackman’s character. “[Chazelle] wanted to look at the [Whiplash] finale in the same way.”

Don Ellis did a (great) score for The French Connection. If the team is imitating Connection, now the Ellis “Whiplash” makes more sense for a “jazz” movie. Again, total speculation.

Ba Da Boom 3: I originally meant to tie the “devotional” idea into the Black Church but I just don’t know enough. However, spirituals and diverse Black Church music are of course essential for the classical jazz aesthetic. I bet in 1920 the grooviest music in America was the Black Church on Sunday morning.

In recent times a drumming style called “Gospel Chops” has emerged. I am not an expert, but here it seems like being fast and flashy is the goal. There are even competitions.

It is interesting that the name “gospel chops” invokes not just devotion but also proprietary racial rights in the manner of hip-hop.

Ba Da Boom 4: My favorite stage band drumming moment is Don Lamond on Bobby Darin’s “Beyond the Sea” (1959). Those fills are just too much. Totally immortal drumming.

Ba Da Boom 5: I brought up Lamond’s “Beyond the Sea” to Steve Little in our interview. That whole interview is relevant to this piece. Little says of his time with Ellington:

Once he said regarding drum solos, “Lift your hands higher. You’re making it look too easy.” The old guys used to put on a show. That’s the only thing I remember him saying to me.

Ba Da Boom 6: I love the great rock drummers, who doesn’t? My comments above don’t mean to invalidate any of those masters. However, in the public arena, the weight of rock’s success tends to obliterate the more esoteric aspects of jazz.

I’m intrigued that a list of the very greatest rock drummers would include many English musicians and at least one Canadian, the iconoclastic Neil Peart. There is frequently something lonely and pagan about the best rock.

Ba Da Boom 7: My favorite Ed Shaughnessy moment is when he accompanies the “magic” act of supreme music comedian Pete Barbutti. There’s no doubt that being in Doc’s band with Carson must have been so much fun. The Hollywood parties alone…

Ba Da Boom 8: A google of “ta-nehisi coates jazz” doesn’t turn up much. In a 2008 look at Bill Cosby’s politics, Coates rejects Cosby’s critique of hip-hop:

At times, Cosby seems willfully blind to the parallels between his arguments and those made in the presumably glorious past. Consider his problems with rap. How could an avowed jazz fanatic be oblivious to the similar plaints once sparked by the music of his youth?

If there is one thing certain in this world, it is that criticizing hip-hop brings intense criticism right back. I make a point of distancing myself from Wynton Marsalis’s scathing comments (“Suppose you saw a group of people who produced the greatest music and musicians in the world and at the end of it you end up with less than the scraps on the table”) in our interview.

However, at the risk of sounding defensive or even arrogant, I just don’t buy the equation I’ve heard so often, and that Coates hints at when discussing Cosby—that black music was jazz then, and that black music is hip-hop now. Jazz and hip-hop are different things, with different relationships to the culture.

At its worst, this kind of thinking seems to encourage not even knowing the basics about Ellington, Monk, Miles, Coltrane. Getting in there for real can only help anyone trying to parse America.

Ba Da Boom 9: I had originally made Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood” the poster boy for unbluesy white blues. However, Hyland Harris informed me that the black Edgar Hayes Orchestra made the first recording with—get this—Kenny Clarke on drums! (Composer of “Mood” is debated. FWIW, Wikipedia.)

I’m still bewildered, so I replaced “In the Mood” with “Tuxedo Junction.” That is also a black piece first played by black orchestra Erskine Hawkins.

It would be a worthy essay to look at the black versions vs. the Miller versions.

Ba Da Boom 10: A familiar jazz story about Elvin Jones tells how Elvin came to New York to audition for Benny Goodman. At the audition he had to play “Sing, Sing, Sing,” a song Elvin didn’t like, and Elvin didn’t get the gig.

Elvin told that story himself. As with many anecdotes related by the black jazz masters, there are subtleties encoded for the cognoscenti.

While working on this post I discovered a long interview with Elvin from 2003. It’s exceptionally valuable. While in the military, he wrote the snare cadences, but when they marched, he played a different instrument.

I played the bass drum because nobody had the will to do it. I was the one that said, —I don’t mind playing the bass drum, because I like to listen to the cadence and the bass drum is essential to the cadence. If you don‘t hear that the cadence isn’t being played right and you lose the time, and everyone gets frustrated. So it’s important.

Being able to write the cadence yet preferring to play the bass drum seems like an ideal perspective for a devotional drummer.

Elvin also mentions Buddy Rich (in a positive light) a few times in this interview.

Ba Da Boom 11: Through an approving link by Jamelle Bouie, I found this discussion of homophobia in Whiplash by J. Bryan Lowder. That’s a worthy topic. But those homophobic rants clearly belong to the genre of locker room talk. Whiplash is really a sports movie, not a jazz movie.

Transferring locker room homophobia onto jazz is a stretch. Lowder writes:

What is it about jazz, as a specific social context, that encourages us to accept homophobia within its confines so readily?

and,

“Harried” and “combative” are pretty apt descriptors for how jazz has historically engaged with the pansy-artist trope.

Huh? It seems like Lowder googled, “jazz homophobia” and came up with two recent articles by Francis Davis and James Gavin. These pieces (by critics I have questioned on DTM before: Gavin, Davis) do not make up “story” about jazz.

I directly challenge Gavin’s piece in particular, which leads with an unnamed white guy who clearly has a personality problem.

My own impression is that classic mid-century black jazz musicians were more forgiving of homosexuality than society overall. This only makes sense, as that community was comprised of outcasts already. I’ll supply a list of great gay black jazz musicians if Lowder needs one, as well as plenty of spicy hearsay.

Ba Da Boom 12: Back to the photos of Buddy, Tony, and Elvin at the top. These two photos don’t deserve the weight I’m going to give them now, but I just can’t resist.

When I see those impeccably turned out devotional black masters posing with the sweating white athlete, my hackles begin to rise. It’s not just the drumming, it’s the whole relationship they were afforded to their work in the 20th century.

Again, this is unfair. I’ve certainly seen Elvin Jones sweaty in a T-shirt with a towel around his neck after a gig!

Still, my fear is that Whiplash slouches in as a sweaty white athlete and blocks our view from the devotional black masters. Seeing those photos unlocked this start of this essay.

It also gives me another opportunity to link to Emily Bernard’s brilliant essay “Teaching the N-Word.” (At one moment, Bernard discusses how she feels dressing up at a college where her fellow white male teachers dress down.)

—

Again, this page is paired with Mark Stryker’s guest post, “Traps, the Drum Wonder.”

—

UPDATE: In the wake of this post, I received the following email from Russell Scarbrough with many more interesting details about Hank Levy, “Whiplash,” and Buddy Rich. Russell agreed to let me post it here. http://www.russellscarbrough.com/

Hi Ethan,

This whole Whiplash thing has brought back a lot of memories!

Hank Levy was a very inspiring, gentle guy, so very much different than the guy in the movie. He was very well known in jazz ed circles in the 70’s & 80’s through his association with Stan Kenton & Don Ellis, but not much of a self-promoter, so a lot of the things he was into just sort of disappeared.

I studied composition with Hank at Towson State from ’90-’94, and played in the band there the whole time. We played only his charts (which we all loved). Many were the odd-meter charts he wrote for Ellis and Kenton – which is what he’s known for almost exclusively – but he also had tons of quite innovative arrangements of standards which are practically unknown.

Quite a bit of the rock-oriented stuff those bands were doing (including Buddy, Kenton, Ellis, as well as Woody Herman, et al) were at the very strong suggestion of their management and record labels. Don Ellis’s Connection album, for instance, was really a scandal among the arrangers who all felt strong-armed into doing assigned pop charts. For a time, they also thought odd meters were the way everything was going to go, so Buddy’s management thought he should get some of that. So some calls were made, and Hank was asked to write something for Buddy’s band.

Hank came up with a chart in 7/4 called “Ven-Zu-Wailin”, an Afro-Cuban kind of tune, and sent it out to LA. The story goes that Buddy didn’t really read charts. When a new arrangement came along, Buddy hired a session drummer to read down the chart in rehearsal with the band while he listened, then he would take over and he’d have it memorized (so the story goes).

Apparently this time (late 60’s), the session drummer couldn’t really get the feel, and the figures and set-ups were all over the place, and it just wasn’t working. The record company guys were there (guess they wanted to record soon), and Buddy tries to play it anyway, and he doesn’t get the feel either. So in a rage, he grabs the chart off the stand and flings it across the room and lets it be known what he thinks about odd meters (your imagination can fill in the blanks there).

So whenever I showed up for lessons with Hank, I would see the framed letter up on the wall of his office on Pacific Jazz letterhead, saying we’re so sorry, but “Ven-Zu-Wailin” was “a little too different” for Buddy and the band, and they were returning the chart, we hope you find a good home for it, sincerest apologies, etc. And this crumpled-up chart came in the package with it. Hank LOVED that story.

Too bad, cause that probably would have sounded great. Hank later re-wrote in 4/4 and we recorded it – it was a burning chart.

We did play “Whiplash” all the time with Hank. It was one of the best-recorded charts of his, and Ralph Humphrey had a lot to do with that, but Ellis’s band in general was much better on Hank’s tunes than the Kenton band, which was frankly terrible (except when Peter Erskine was in the band). I haven’t seen the movie to know if they played it, but the back half of that chart is written in 14/8, because the subdivision is 223322 – a really nice-feeling pattern that Hank said explicitly came from Bulgarian music, and which he used fairly often. Those different subdivisions of the asymmetrical meters are what has been lost lately outside of world music stuff, but Hank and Ellis were very interested in that. A lot of their most interesting experiments in that were never recorded, but we did some of those things – big band charts with 2 drum sets playing in different subdivisions at the same time, for instance.

We also played a lot of straight-ahead swinging in 5, 7, and other asymmetrical meters. Not 5/4 as in the “waltz+2” feel of “Take Five,” but just 5-on-the-floor swinging. Hank’s “Chain Reaction” for Ellis has a blistering straight-ahead 13 section for pianist Milcho Leviev to blow over (not long enough, but enough to prove that it can be done, and done well). He also had a few things that were overt homages to the Basie style, but in 5/4. I don’t hear much of that kind of thing lately, though in some quarters odd meters are otherwise ubiquitous.

In regards to the substance of your post, it would be an interesting comparison to look at the elaborate “drum routines” of the Don Ellis band, which were virtuosic for sure, vs the vaudeville-like solos of Rich. Personally I find Rich’s solos repetitive and hackneyed at best, and a true annoyance at worst. On the Roar of ’74 album, which is a fantastic band playing really great arrangements, he basically plays a drum solo throughout every every tune, even where the charts have space to breathe built in – he just bashes right through. And then plays another solo at the end. If you ever want to see Bill Holman roll his eyes and shake his head ruefully, ask him about the charts he sent Buddy, and how they turned out on the record.

The genius of Mel Lewis is the perfect antidote to Rich-ophilia.

Best Regards,

Russell Scarbrough

—

UPDATE 2 and 3: Jaleel Shaw (jaleelshaw.com) offered some penetrating commentary on Twitter; with his blessing I’m reproducing it here.

AND: A day later, Jaleel stepped up his game further with a whole post on his blog concerning these issues. Check it out.

I read your post on Whiplash. Just wanted to address the part about “black intelligentsia not being interested”

For one, I think we have to remember there was a time when blacks couldn’t use the same entrance to clubs as whites

If a club told me I had to use a separate entrance, I still wouldn’t want to go to that club once things changed.

We also have to remember that there used to be clubs in black communities (like Harlem) that blacks went to & even owned

Of many things that have changed, It’s very clear that there aren’t many “jazz” clubs in black communities any more.

We also have to consider education. I never learned about “jazz” or anything that had to do with my culture in grade school.

Luckily I had a mother that was into this music & exposed me to it & other styles of music at a young age.

In school, the learned about Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart.

I love Bach, but looking back, I wonder why I wasn’t taught about Bird, Ellington, & other American musicians in school.

I was a music ed. major at Berklee. When I went to do my student teaching I noticed the urban schools had no music classes.

Meanwhile, the suburban schools were learning all about Ellington, Monk, Armstrong and other American musicians/composers

Almost of of the suburban schools I visited didn’t have many if any black students. The urban schools were all black.

I can’t say this is exactly why “many in the black intelligentsia aren’t interested” in jazz, but I think it’s beyond a start.

—